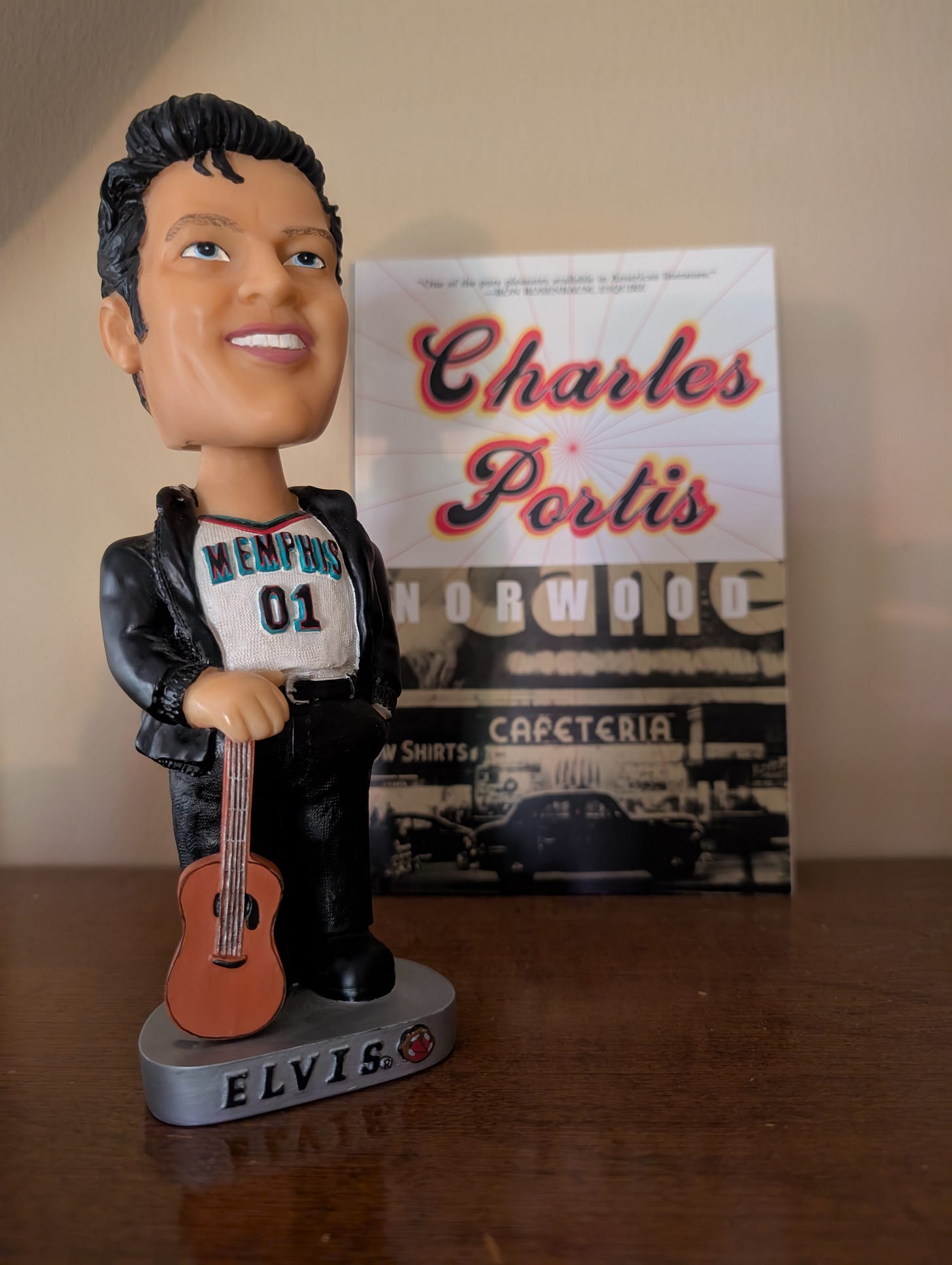

When Charles Portis met Elvis

A cub reporter and the boy king meet in 1958 Memphis

Summer of 1958, a decade before Charles Portis published his novel TRUE GRIT, he was a reporter for The Commercial Appeal, the Memphis daily, assigned to cover Pvt. Elvis Presley’s emergency leave from Fort Hood to visit his sick mother, Gladys:

Leaning on a windowsill in the hallway (of Methodist hospital) yesterday, he reflected moodily on the family’s pre-Cadillac days: “I like to do what I can for my folks. We didn’t have nothin’ before, nothin’ but a hard way to go.”

About that time a small fat boy appeared and asked Elvis for an autograph. He grinned and ran his hand through the boy’s hair and said in flawless diction, “You little rascal. You were standing there all that time and didn’t say anything. Let me see that pencil.”

He was talking to his public again. He was Elvis Presley again.

Portis was 24 — only about a year older than Elvis — but already he was good. That knack for telling details, those small moments that show us some larger truth. I wonder how many reporters, especially at that age, would have caught Elvis’s flipped switch to “flawless diction.” Even that description of the boy, the seemingly at odds “small fat,” which makes you stop and try to picture the kid in your mind. Well, I did. Also, that last line — a perfect walkaway.

Near as I can tell, Portis only spent about six months in Memphis. The last byline I can find in The Commercial Appeal archives was from December 1958, a front-page account of a late-night fistfight at a Christmas party between the president of a civic club and an off-duty police captain with the improbable name of Jewel W. “Joe” Slaughter.

Punches were thrown, a pair of glasses broken, five teeth gone missing. Portis played it straight, as a reporter must in a news story, but he got in a sneaky little jab of his own:

“Both men are in the six-foot, 200-pound division.”

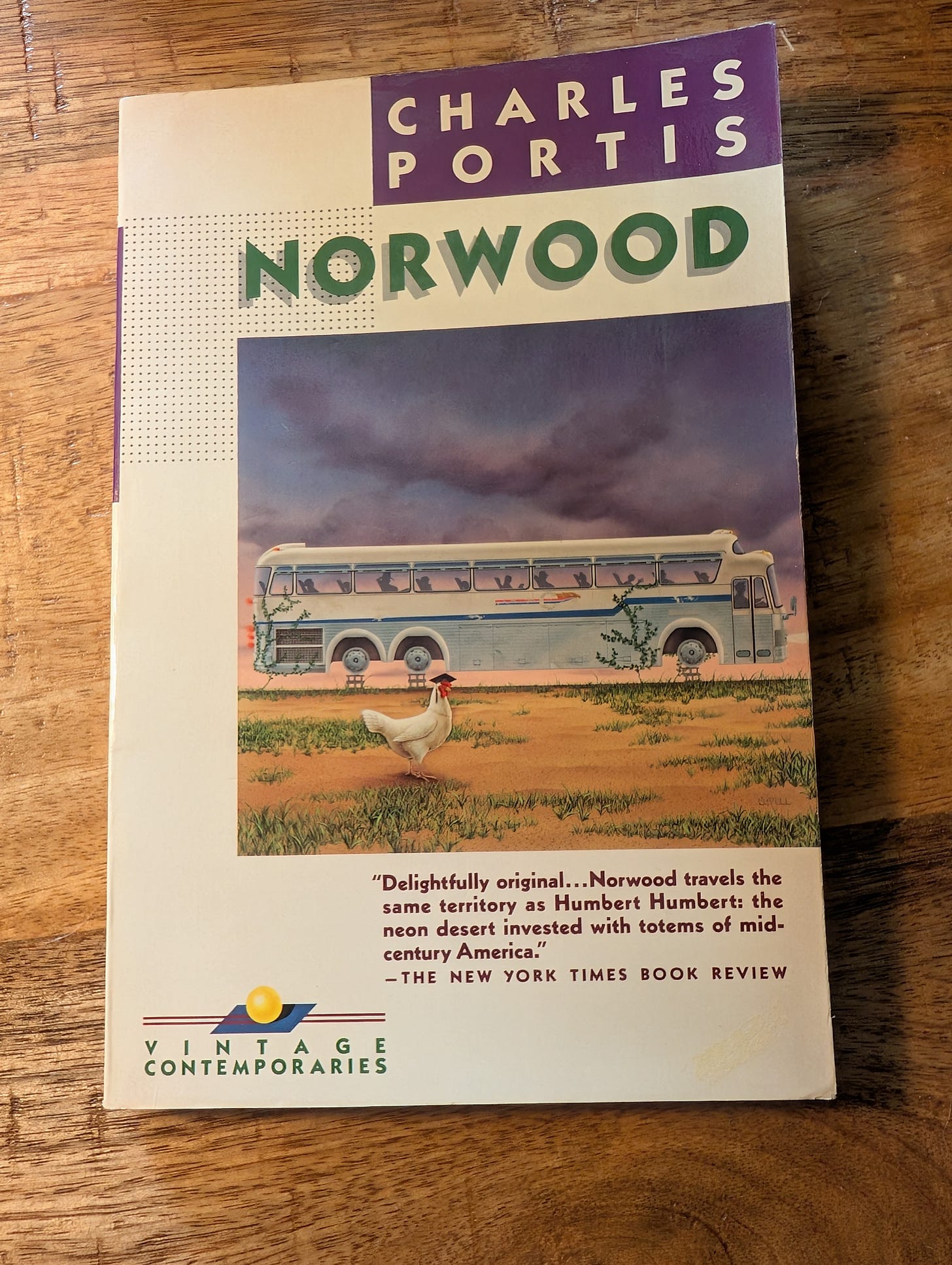

Portis went on to bigger things, as they say. As a newspaperman with the New York Herald Tribune, he covered the civil rights movement in his native South and later became the paper’s London bureau chief; as an author, he wrote some of the best comic novels you could hope to read. TRUE GRIT is the most famous, but start with NORWOOD, his first, the one with the college-educated chicken. My favorite is the picaresque DOG OF THE SOUTH, where the narrator, Ray Midge, tells us about all the interesting things he sees out on the road:

The third interesting thing was a convoy of stake-bed trucks all piled high with loose watermelons and cantaloupes. I was amazed. I couldn’t believe that the bottom ones weren’t crushed under all that weight, exploding and spraying hazardous melon juice onto the highway. One of nature’s tricks with curved surfaces. Topology!

Portis had found his calling as a writer of absurdist-if-straightfaced fiction. America’s “least-known great writer,” said Esquire. “Like Cormac McCarthy, But Funny,” per the headline in The Believer.

Still, as an old former reporter myself, as a near 30-year veteran of The Commercial Appeal, I can’t help but lament journalism’s loss. I also can’t help but wonder to what extent Portis the newspaperman helped make Portis the novelist.

Yes, I say this knowing Portis famously said he majored in journalism at the University of Arkansas because “I must have thought it would be fun and not very hard, something like barber college.”

But I also remember what novelist Donna Tartt, who recorded the audiobook version of True Grit and came to know Portis, wrote in The New York Times, after his death in 2020:

His preferred subjects were local history, his boyhood in Arkansas, his time in the military … and above all his life as a newspaperman (somewhat perplexingly to me, he regarded himself mainly as a former newspaperman instead of the major and singular American novelist he was).

In 2017, as an editor on a project commemorating the 40th anniversary of Elvis’s death, I tried unsuccessfully to interview Portis, who was famously private and media adverse.

I had wanted to ask him about Elvis, of course, but also about his newspaper days, especially those first ones out of college, in Memphis. I wanted to ask him about those heady days in The Commercial Appeal newsroom — his Sun Studios, if you will, his launching pad. That place where a Southern boy wonder first showed the world his stuff.

Bonus material:

I made my request to interview Portis via an Oxford American editor I knew a little, Jay Jennings. He was a long-time friend of Portis, and a Portis scholar who would eventually edit The Library of America’s CHARLES PORTIS: COLLECTED WORKS.

He emailed back to say Portis’s heath was too poor at the time, but added:

I do remember him telling me that he happened to be on the police beat and checking the hospital (for crime victims) the night Elvis arrived from his army posting and in his uniform to visit his mother there after she’d been hospitalized. He approached Elvis and the King’s henchman closed ranks. Portis said, “I’m with The Commercial Appeal,” and Elvis replied, “Let him through, The Commercial Appeal’s always been good to me,” and so he got the scoop for the CA.

In 1973’s THE NEW JOURNALISM, Tom Wolfe wrote about his Herald Tribune colleague Portis as “the original laconic cutup,” and related a story about the time Portis was invited onto “a kind of ‘Meet the Press’ show’ with Malcolm X, who lectured the reporters in advance that his name was Malcolm X, and he was not to be called simply Malcolm, because, as Wolfe tells is, he was not a dining-car waiter.

Here’s what happened, according to Wolfe:

By the end of the show Malcolm X was furious. He was climbing the goddamned acoustical tiles. The original laconic cutup, Portis, had invariably and continually addressed him as “Mr. X.”

Later, Wolfe related how Portis, then in the paper’s London bureau, “quit cold one day. … He returned to the United States and moved into a fishing shack in Arkansas,” wrote “a beautiful little novel” called NORWOOD and then the bestselling TRUE GRIT.

He sold both books to the movies … He made a fortune … A fishing shack! In Arkansas! It was too goddamned perfect to be true, and yet there it was.

Further reading:

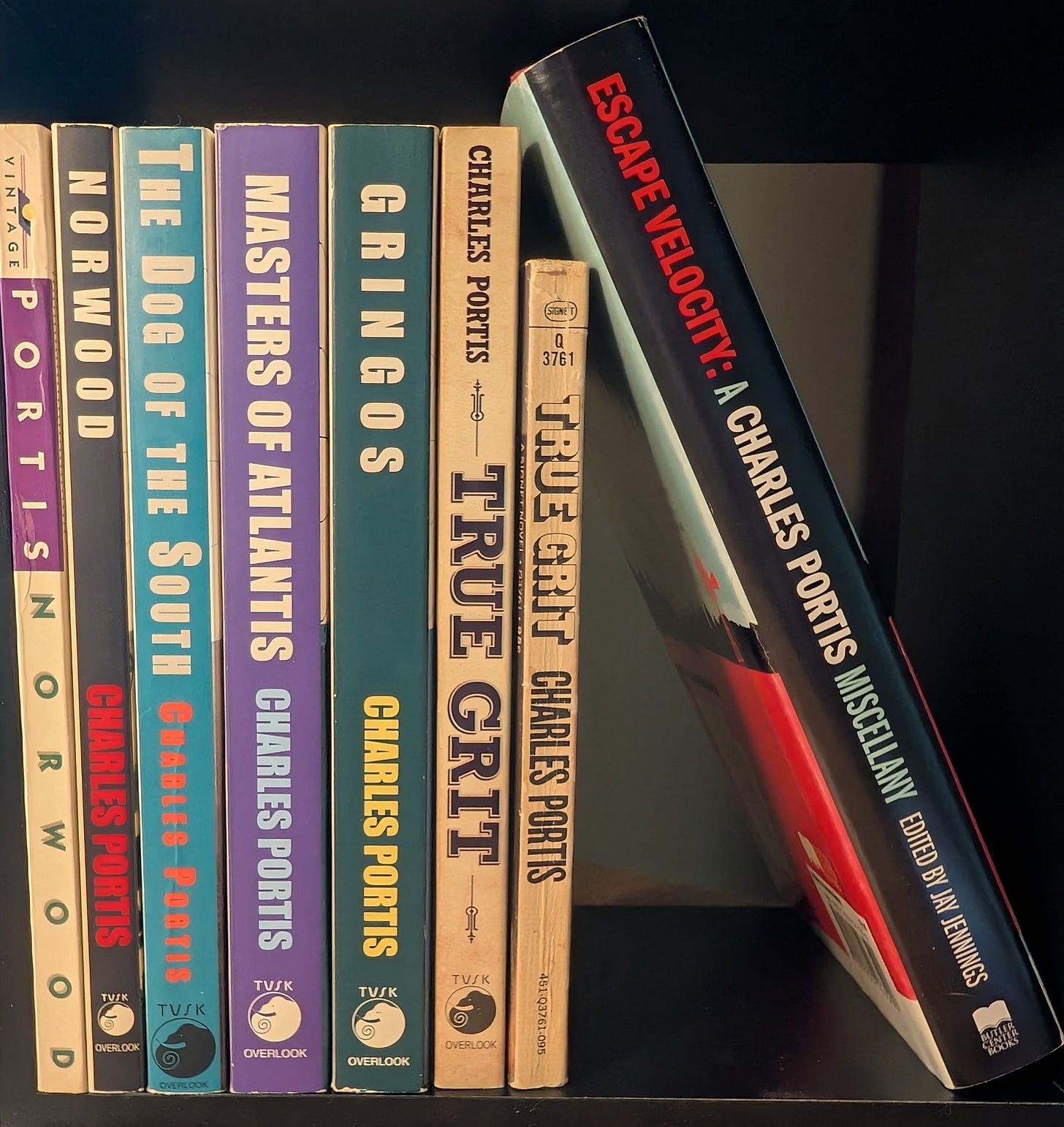

All five novels, of course: NORWOOD, TRUE GRIT, THE DOG OF THE SOUTH, MASTERS OF ATLANTIS, and GRINGOS.

The Library of America’s CHARLES PORTIS: COLLECTED WORKS, which includes the novels, plus short stories, reporting and other writing. Edited by Jay Jennings.

ESCAPE VELOCITY: A CHARLES PORTIS MISCELLANRY, also edited by Jennings and including a selection of Portis’s work for The Commercial Appeal.

“Like Cormac McCarthy, But Funny,” by Ed Park in The Believer.

“Donna Tartt on the Singular Voice, and Pungent Humor, of Charles Portis,” The New York Times

“The Shaggy Dog of the South,” a short appreciation of my favorite Portis novel, here on South Bound.

Excellent reminder of Portis’s singular genius. I used to teach Gringos to high school seniors—those were the days! I also have a stack of letters from CP, typed on his manual typewriter, that I’ll share sometime on this platform.

Love all the novels but my single favorite thing by Portis might be Motels, Lower Reaches in the Collected Works.

"I drove up to Truth or Consequences on a whim, going out of my way to look around. I could find no trace of the old yellow cabins, not even locate the sight. Things disappear too, utterly. "

Charles Portis actually is who people think Hemingway is....the man just simply wrote the best sentences.